Biography of M.C. Escher

This biography is condensed mostly from the biography written by Bruno Ernst for the book M.C. Escher - His Life and Complete Graphic Work, © 1981, with some material from original essays by M.C. Escher.

Early Life

Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher was born on June 17, 1898, in the Dutch

province of Friesland. His parents, George Arnold Escher and Sarah

Gleichman Escher, had three sons of which Maurits (called Mauk for

short) was the youngest. His father, George, was a civil engineer. The

Escher family was living in Leeuwarden in 1898, where George served as

Chief Engineer for a government bureau. The family lived in a grand house

named "Princessehof," which would later become a museum and host

exhibitions of M.C. Escher's works.

Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher was born on June 17, 1898, in the Dutch

province of Friesland. His parents, George Arnold Escher and Sarah

Gleichman Escher, had three sons of which Maurits (called Mauk for

short) was the youngest. His father, George, was a civil engineer. The

Escher family was living in Leeuwarden in 1898, where George served as

Chief Engineer for a government bureau. The family lived in a grand house

named "Princessehof," which would later become a museum and host

exhibitions of M.C. Escher's works.

Young M.C. Escher moved with his family to Arnhem. He attended elementary and secondary school there, and also in the seaside town of Zandvoort, where he lived for a while to improve his health. In 1907, he started learning carpentry and piano. In secondary school, his marks were poor except in drawing. His art teacher took and interest in his drawing talent, and taught him to make linocuts. He failed his final exam and thus never officially graduated.

In 1913, M.C. Escher met his lifelong friend Bas Kist in religious school (which he attended at his parent's direction, even though he wasn't very religious). Kist was also interested in printing techniques, and may have encouraged M.C. to make his first linoleum cut works. Amoung these early works is a portrait of his father which is the oldest surviving work by the artist. In 1917, the two friends visited the artist Gert Stegeman, who had a printing press in his studio. Some of M.C.'s work from this year were apparently printed at Stegeman's.

Also, in 1917, the Escher family moved to Oosterbeek, Holland. During this year and the following few years, M.C. Escher and his friends became very involved in literature, and M.C. began to write some of his own poems and essays.

In 1918, Escher began private lessons and studies in architecture at the Higher Technology School in Delft. He managed to get a deferrement on military service in order to study, but poor health prevented him from keeping up with the curriculum. He was rejected for enlistment in the military service in 1919, and as a result could not continue school (he had never successfully graduated from high school!). During this difficult period, Escher did many drawings, and also began using woodcuts as a medium. It was also at this time that his work began to receive favorable reviews in the media.

Still trying to pursue a career in architecture, M.C. Escher next moved to Haarlem and began studies as the School for Architecture and Decorative Arts. After on a week in the city, he met the artist Jessurun de Mesquita. After seeing Escher's drawings, Mesquita and the school's director advised him to continue with them. He began full-time study of "the graphic and decorative arts" in the fall of 1919. Also at this time, he acquired a white cat as a present from his land-lady.

In 1921, Escher and his parents visited the Riviera and Italy. Unimpressed by the tropical flowers of the mediterranean climes, he made detailed drawings of cacti and olive trees. He also sought out high places and dramatic vistas to sketch, some of his later works were influenced by these sights.

Escher started to experiment with themes that would suffuse his later works around this time. The woodcuts he did for a humorous booklet Easter Flowers exhibit several: mirror images, crystal shapes, and spheres.

The first print by M.C. Escher to sell in large numbers was St. Francis (Preaching to the Birds), a woodcut that Escher claimed to have "worked on like a madman." He finished out the year doing some sign work and a few commisioned prints. In 1922, in search of fresh inspiration, he decided to go to Italy.

Italy and Spain

M.C. Escher and two friends left Arnhem for Italy in April of 1922. On his leaving, his mother had these words of parting for her artistic son: "Son, don't smoke too much." The two friends returned to Holland after only a couple of weeks in Florence, and Escher went on to San Gimignano with a sister of one of them. He did a great deal of serious drawing here and in the next few towns he visited: Volterra and Siena. He spent all of the spring of 1922 roaming the Italian countryside, drawing landscapes, plants, and even insects. In Assissi he met a fellow Dutchman, the painter Gerretsen. The two met occassionally over the next few years.

Returning home in June, Escher found that he could not be happy and productive in his old environs. He seized his first opportunity to return to southern europe, taking a freighter to Spain with some friends, and saving expenses by caring for their two small children on the trip. It was on this trip that he first saw the phenomenon of a phosphorescent sea, so beautifully expressed later in his woodcut of the same name. In Spain, he saw his first bullfight: an "off-putting and barbaric" event. He visited Madrid and its famous museum, the Prado, but was unimpressed by many of the paintings there. Surprisingly, he also attended another bullfight. He dodged large rats to find a place to draw in Toledo. Missing an express train, he spent 24 hours on a local train to get to Granada. In Granada, Escher visited the Alhambra, and saw examples of Moorish (Arabic) decorative styles. He studied these, and copied one.

Escher travelled from Spain to Italy by ship, and enjoyed the voyage immensely, splitting his time between drawing the ship and playing cards with her officers. After travelling around Italy, he settled in Siena for several months. During this time he worked very hard and enjoyed himself immensely, calling the town and atmosphere "blessed."

March of 1923 found Escher still working hard and traveling around Italy. At the end of the month, a Swiss family took up residence at the pension where Escher was staying. Over the next few months, Escher found himself drawn to the daughter of the family, Jetta Umiker. Letters to his friend Jan state that he found her arms especially attractive. In a more serious vein, Escher realized he was falling in love with Jetta Umiker, but was uncertain of his own ability to maintain a relationship. When the Umiker's left for Switzerland in June, Escher expressed his feelings at the last moment, and a bond was formed.

Escher traveled around Italy some more, and in August of 1923 held his first one-man show in Siena. He paid very little attention to this important milestone in his artistic career, he was concentrating on Jetta. In mid-August he proposed to her, and on August 28 arrived in Zurich to formally meet the family. They decided to marry and live in Italy.

1924 was a very busy year for M.C. Escher. He held his first one-man show in his native Holland in February. On June 12, he married Jetta in Viareggio, Italy. The newlyweds visited Genoa, Annecy, and Brussels. In October they went to France, and then went back to Italy. During all these travels, Escher had the chance to observe a great many architectural forms. At the end of 1924, Escher and his new bride purchased a house under construction in Frascati, a small town outside of Rome. The house was finished in March, 1925, but the couple did not move in until October.

Shortly after Escher moved into his new home outside of Rome, his brother was killed in a mountaineering accident, and Escher had to go to the site to identify the body. After this tragedy, Escher produced his famous Days of Creation woodcuts.

In June of 1926, the Eschers bought a new, larger house under construction in anticipation of an addition to their family. In late July, George Escher was born. It is a measure of Escher's growing fame that both King Emmanuel and Mussolini attended the boy's christening.

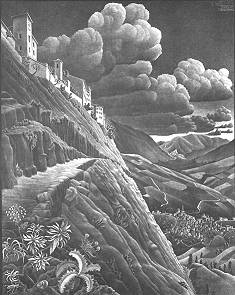

Living

in Rome, happy with his wife and child, the late 1920s were a productive

period for Escher. He exhibited works in many shows in Holland, and by

1929 was so popular that he was able to hold five shows in Holland and

Switzerland that year. It was during this period that his pictures were

first labeled as mechanical and "reasoned." Pictures from this

period include some of Escher's most striking landscapes, and also some

stark commercial illustrations. The very famous lithographic of a

mountainside village, Castrovalva, was completed in February 1930.

Also, Escher's son Arthur was born in 1930.

Living

in Rome, happy with his wife and child, the late 1920s were a productive

period for Escher. He exhibited works in many shows in Holland, and by

1929 was so popular that he was able to hold five shows in Holland and

Switzerland that year. It was during this period that his pictures were

first labeled as mechanical and "reasoned." Pictures from this

period include some of Escher's most striking landscapes, and also some

stark commercial illustrations. The very famous lithographic of a

mountainside village, Castrovalva, was completed in February 1930.

Also, Escher's son Arthur was born in 1930.

Later in 1930, and into 1931, Escher health was poor and there was a lull in the sale of prints. These lulls occured periodically through the artist's life, this time it was broken by a meeting with the Director of the Dutch Historical Institute in Rome. G.J. Hoogewerff suggested some new works, and also wrote an article in a magazine about Escher's work. The works he suggested were published as a book, Emblemata, in 1932.

The printroom of Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam bought twenty-six prints to give Escher a nice start to 1933. In May, he went to Corsica and made nineteen drawings that later became wood engravings and lithographs. Later that year, he created some prints for a horror book named The Terrible Adventures of Scholastica.

In 1934, Escher and his family went to the seashore, and then Escher and his wife continued on to Belgium, Ghent, and Bruges. In the meantime, his work was doing well in the US. His print Nonza won third prize at the Exhibition of Contemporary Prints at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute also purchased the print, which was Escher's first sale to a museum in America.

Back to the North

Due to business in Holland, Escher traveled to his parent's house at The Hague in the summer of 1935. He then travelled to Amsterdam. During this visit, Escher spent a great deal of time on a detailed portrait of his father. This lithograph was finished in August, and prints given to members of the family only.

In August of 1935, Escher and his family moved into a new home in Chateau-d'Oex, Switzerland. Life was expensive, and Jetta missed the social life of Italy. Escher worked hard, and finished several woodcuts and a lithograph.

As autumn passed into winter, the Escher family grew accustomed to their new home. Jetta took up piano again, and Escher himself joined the local chess club. The children enjoyed the snow. In December, Escher made a lithograph of a farmer's shed on a snow-covered hillside, but was disappointed with the poverty and starkness of the result. His son George later said that his father missed the warmth of Italian landscapes.

In early 1936, Escher was determined to take a trip back through southern Europe. He wrote a shipping company, and offered to make prints of the company's ships and their ports of call, in exchange for free passage on the company vessels. To his surprise, the Adria shipping company accepted the offer, and at the end of April he left for Trieste. At the Adria offices, he was treated with great deference and courtesy.

Escher's journey by ship took him to Venice, Ancona, Bari, Catania, Palermo, Genoa, and several other Italian and Sicilian cities. Jetta joined him in mid-May. During the trip, Escher made many sketches of the ships and ports. Roughly nine prints, almost all woodcuts, resulted from the trip. It was to be Escher's last extended trip through his beloved Mediterranean Italy.

In June, after his trip courtesy of Adria, Escher and his wife visited some lakes in Switzerland, and then went to stay with Escher's parents at the Hague. The trip was successful, but it was a successful ending to one phase of Escher's career. On September 1, Escher and his family returned to Chateau d'Oex, and Escher's graphic work gradually began to take new directions.

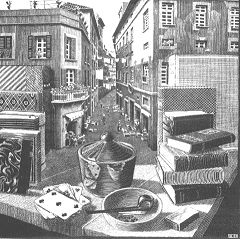

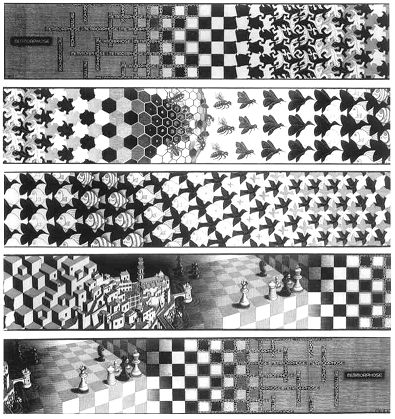

Metamorphosis

By the end of 1936, Escher had finished most of the prints for the Adria company. One of the other works during this time was based on a sketch from the trip: it was Escher's first print of an impossible reality, called Still Life with Street. He had begun to think more about artistic expression from images in his mind, rather than directly from his observations and travels.

Also in 1936, Escher visited Alhambra for the second time, again studying the Moorish tilings. This visit, plus his departure from Italy, can be seen as forces which pushed him in new directions. In a 1960 book introduction, he wrote the following.

The fact that, from 1938 onwards, I concentrated more on the interpretation of personal ideas was primarily the result of my departure from Italy. In Switzerland, Belgium, and Holland where I successivly established myself, I found the outward appearance of landscapes and architecture to be less striking than those which are particularly to be seen in the southern part of Italy. Thus I felt compelled to withdraw from the more or less direct and true-to-life illustrating of my surroundings.

These personal circumstances, caused in part by the brewing war, were in large part responsible for Escher turning inward for vision.

In mid-1937, the Escher family resettled in Ukkel, a suburb of Brussels, Belgium. In October, Escher showed his brother Beer the plane-filling tilings he had been working on. Beer, a professor of geology, was apparently impressed with work and with the potential applications to crystallography.

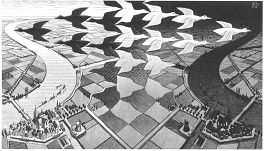

In 1938, Escher continued to experiment with plane-filling techniques, shapes, and transformations. In order to give the impression of infinite extent, he tried first tried making the figures more vague toward the edges of the print, and later by scaling the figures smaller as they approached the center, or smaller as they approached the border. One of the most beautiful motifs Escher created was that of two birds flying in opposite directions. This became the basis for the famous print Day and Night, which is still one of his most popular single works.

On June 14 1939, M.C. Escher's father, G.A. Escher, died in his home in the Hague.

Several months after his father's death, Escher began work on a new major work. He had already done a woodcut named Metamorphosis [1937], it showed a city block transforming into a little human figure. The new Metamorphosis II was to show a sequence of ten transformations, and at 19cm x 3.9m it was his largest print. As another experiment with tilings, he carved a motif of swimming fish onto a beechwood sphere, completely covering the surface. Escher was extremely fond of this little sculpture, keeping it with him the rest of his life.

In May 1940, the Nazi army invaded Holland and Belgium; Brussels and its suburbs were occupied on the 17th. At the end of May, Escher's mother died. Due to the invasion, he missed her funeral at The Hague. Escher spent the rest of 1940 settling his mother's affairs, and executing a commission to decorate the town hall of Leiden. He and Jetta found a house in Baarn, Holland, and moved there in February of 1941.

Holland, The War, and Fame

The Nazi persecution of the Jews touched Escher in a very personal way. His old teacher, Samuel de Mesquita, a Jew, was taken away by the Nazis in January of 1944, and was killed. Escher helped to transfer Mesquita's works at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. He kept for himself a sketch that bore the imprint of a German boot, and kept it with his drawing supplies for the rest of his life. In 1946, he organized a memorial showing for Mesquita at the Stedelijk

Immediately after the war ended, Escher participated in a show of works by artists who had refused to collaborate with the Nazi regime. Afterwards, he earned several new commissions, including one to make 400 copies of one of his prints for distribution to schools.

In 1946, Escher became interested in a new technique: mezzotint. While very laborious and time-consuming, the resulting works could show very subtle and delicate lines and shadings. Possible one of Escher's most famous mezzotint works, and one that shows off the technique well, is the 1948 Dewdrop.

In 1949, Escher and two other artists held a major exhibition in Rotterdam. In addition to showing their prints, all of the artists gave talks and demonstrations about their technique. Escher sold dozens of prints, including one of the huge Metamorphosis.

In addition to doing woodcuts, lithographs, and an occasional mezzotint, Escher took on several unusual commissions in 1949/1950. Working with a weaver, he designed a tapestry, and at the request of manufacturing giant Philips of Holland, he designed a ceiling decoration for a factory (in celebration of the firm's 60th anniversary). It is a good measure of Escher's growing fame that he was beginning to get as many requests for these kinds of services as he could handle. Although some serious print collectors in America knew about Escher's work, he was not yet popular outside of Europe.

Fame in America began for Escher with two magazine articles. Due to recognition in the art journal The Studio, Time-Life journalist Israel Shenker interviewed Escher at his home in Baarn. The interview took place in late 1950, and articles about Escher and his work appeared in the 4/2/51 Time and the 5/7/51 Life. The articles gained some attention, and orders for Escher work increased greatly.

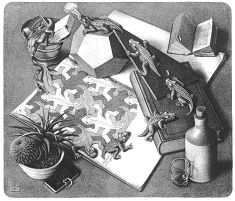

Escher

sometimes crafted models or figures in clay, wood, string, or other

material to assist himself in visualizing subjects of his prints. For

example, the famous Reptiles from 1943 depicts a tiny crocodile crawling

out of a tesselation and over some books; according to his George Escher,

the little croc was crafted from plasticine and posed with some items

found on a desk. In 1951 Escher created a peculiarly compelling lithograph

named House of

Stairs which featured an odd little animal. Escher modeled the "curl-up"

in clay prior to beginning the lithograph.

Escher

sometimes crafted models or figures in clay, wood, string, or other

material to assist himself in visualizing subjects of his prints. For

example, the famous Reptiles from 1943 depicts a tiny crocodile crawling

out of a tesselation and over some books; according to his George Escher,

the little croc was crafted from plasticine and posed with some items

found on a desk. In 1951 Escher created a peculiarly compelling lithograph

named House of

Stairs which featured an odd little animal. Escher modeled the "curl-up"

in clay prior to beginning the lithograph.

Gaining Popularity

Also during the early 1950se, Escher gained popularity as a lecturer. He was in demand both for artistic audiences, and for scientific ones. He also held his first one-man exhibition in the United States. It was held in Washington, and raised US awareness of Escher's work and sold many prints. Due to the rush of work, Escher completed only two new works in 1954.

April 27, 1955, was an exciting but morally conflicting day for M.C. Escher. It began normally, with him working on a woodcut in his studio. By the end of the day, he was a Knight! He described it as follows to his son Arthur. This letter captures very well the tone of his personal correspondence during this period, and also his aversion to the trapping of celebrity.

Three days ago the town clerk announced Alderman Ros was coming to visit me the following morning. In view of the warm weather and my being very busy, I had not dressed up in anything special but was working on a woodcut in my old cord trousers and shirt-sleeves, when Mr. Ros come into the studio together with the town clerk. I had no idea whatever why they had come. I thought they might want to buy one of my prints to adorn a wall in the town hall, or I might be given some commission for the municipality. I put on my old jacket, and after shaking hands asked them to take a seat. Mr. Ros replied that he would rather remain standing. Then he proceeded to tell me that the Mayor was indisposed and that he, Ros, was acting in his stead. I wondered why he had to tell me all this standing up, and again asked them to sit down. Ros refused a second time and said they had to remain standing a little longer. I didn't understand it at all. Possibly he had a boil on his backside? Finally he told me the big news: he was honoured to offer me, in the name of our revered Queen, the Knighthood of the Order of Oranje Nassau. As I watched dumbfounded, he took out a beautiful orange box; out came a silver cross inlaid with enamel. He made some unsuccessful attempts to pin this weighty object onto my chest, but he was too nervous - or the safety pin would not go through my lapels. At any rate, your dad is a knight, even if not of the garter. Why in the world they should want to "decorate" me is a complete mystery. I can only hope it is not a mistake. That evening my name was in the paper along with thousands of others who received a decoration in honor of the Queen's birthday. In fact my knighthood does not amount to much. Van Beinum, the conductor of the famouns Concergebouw Orchestra, was made of knight of the Nederlandse Leeuw [a higher order].

But to get back to the point: did you ever imagine that your dad, who lives so far away from the bustle and intrigue of the world, working on his prints day after day like a hermit, would some day be drawn into the sickening scene of vain officialdom, despite himself? However, there is one thing they will never get me to do and that is wear a decoration in my buttonhole. When I'm tired, I occasionally travel second class [equivalent to business class?] on the train and I see one of these important gentlemen wearing his decoration. Their deliberate pose and condescending self-satisfied smiles clearly distinguish them from the sad anonymous crowd with empty buttonholes.

But what on earth can I do about it? Luckily I can swear by God and all his angels that I never moved a finger to get the decoration or licked the boots of any bigwigs.

In 1955 and 56, Escher completed many famous prints, including the beautiful "Three Worlds" and distinctive "Print Gallery". During this time, he also sold many prints. For example, he received a check from a Washington art dealer - bring his total for sales in the US to $2125 for the sale of 150 prints! This sum may seem small today (indeed, some individual Escher works from the 1950s sell for nearly as much) but Escher was well pleased with it.

In 1957, Escher received a commission to do a wall mural in the Dutch city of Utrecht. He worked on this and other projects through most of 1958, also taking another trip around Europe. In October of 1958, his son George finished his University training in engineering, and emigrated permanently to Canada. This was something of a frustrating time of Escher, artistically; several prints he began work on turned out less well than he had hoped. For example, about "Sphere Spirals" he wrote:

After the first proof my high expectations were, as always, greatly disappointed. I am now struggling on - with some feeling of despair - so that I at least achieve a passable result.

In

terms of Escher's work, we can also see a definite trend beginning in

1956-58 toward merging the themes of approaching infinity and tiling the

plane. Beginning with the print "Smaller and Smaller" (1956) and

continuing through "Whirlpools" (1957, shown at right) and up

until his last print "Snakes", Escher sought a way to express

infinity within the bounds of a finite print. Prior to 1958, all save one

of his works show objects shrinking toward the center of the print. After

1958, all such prints show objects shrinking toward the outer edges.

In

terms of Escher's work, we can also see a definite trend beginning in

1956-58 toward merging the themes of approaching infinity and tiling the

plane. Beginning with the print "Smaller and Smaller" (1956) and

continuing through "Whirlpools" (1957, shown at right) and up

until his last print "Snakes", Escher sought a way to express

infinity within the bounds of a finite print. Prior to 1958, all save one

of his works show objects shrinking toward the center of the print. After

1958, all such prints show objects shrinking toward the outer edges.

The change in approach to showing infinity was due in part to Escher seeing an article by Prof. Coxeter of Ottawa, which included an illustration of a system for reducing a plane-filling motif with increasing distance from the center of a circle. Escher interpretation and extrapolations of Coxeter's system appear in no less than 6 major works. Escher found the effect beautiful, but was sometimes worried that viewers would not.

While a small circle of mathematicians had been appreciating Escher's work since the 1940s, it was in 1959 that he met Prof. MacGillavry. This lady academic arranged for Escher to give a talk about symmetry to an international meeting of crystallographers in England. Also in 1959, Escher received from friends a copy of an article by L.S. and Roger Penrose, describing various sorts of 'impossible objects'. The article mentioned some of Escher's older works, and also inspired a few. For example, the very famous print "Ascending and Descending" (1960) is based on the endless stairway described in the article.

Early in 1960, the first book of Escher's prints was released, Grafiek en Tekeningen, with descriptions of 76 works by Escher himself. The book helped Escher gain recognition among mathematician and crystallographers, including some in Russia and Canada. Before even giving his lecture to the Cambridge crystallographers' meeting in August of 1960, Escher also arranged to give it again in Canada and the US. When he finally gave the Cambridge lecture, it was very well-received; Escher also had a great time in England, being a something of a guest of honor at the meeting, and the only artist in attendance.

In the last months of 1960, Escher went on an long trip by freighter to the US and Canada. In addition to giving lectures in Boston and Ottawa, he was able to meet his infant grand-daughter. He made the acquaintance of several professors at M.I.T., some of whom later became friends and good customers. In all, the year 1960 was a very successful one, both artistically and financially; correspondence from that year clearly shows Escher to be in good spirits and very busy filling orders.

The Later Years

Mathematical and crystallographic aspects of Escher's periodic (tiling) works became quite popular in the late 1950s and 1960, and in 1961 he gave permission for a book about them to be published under the auspices of the International Union of Crystallography. The book, Symmetry Aspects of M.C. Escher's Periodic Drawings by Prof. Caroline MacGillavry, was published in 1965.

Could use some more here about the Escher's work in 62 and 63, as well as the planned trip to Boston in 1962 that never took place.

In 1964, Escher went to North America again to see his son and deliver a series of lectures. Unfortunately, he fell ill almost immediately upon arrival, and after surgery in Toronto he and his wife returned to Holland. The lectures, which Escher had written out in full, were published more than two decades later as part of the book Escher on Escher (Abrams, 1986).

Escher's wife was never happy living in Baarn. In 1968 she moved back to Switzerland, and lived there the rest of her life. Escher himself stayed in Baarn, and immersed himself in work. His health was failing, but he continued drawing and printing woodcuts.

In 1970, after another round of surgery, M.C. Escher moved to a new apartment in the Rosa Spier House in Laren, the Netherlands. His new rooms included a studio, but his health was too poor to do much work. He continued to correspond with various friends all over the world, including his boyhood companion Bas Kist. A comprehensive book about his life and work was published in Dutch at this time, and other books were in preparation. Escher lived long enough to see the first book, The World of M.C. Escher, translated into English and become very successful.

During the month of March, 1972, Escher's condition deteriorated. His family gathered around him, taking turns sitting by his hospital bed. On March 27, 1972, he died, at the age of 73.

Text reprinted from http://users.erols.com/ziring/escher.htm